If you

made it this far into the series, congratulations. Whether or not you'll like how it ends is a bit of a coin toss.

If you

made it this far into the series, congratulations. Whether or not you'll like how it ends is a bit of a coin toss.

We learn that the old man at the end of Furious Gulf is none other than Nigel Walmsley. Someone how the jerk protagonist from the first two books managed to survive some 30,000+ years (time dilation and really advanced technology helped) and is now present to help Toby escape the Mechanicals that have been pursuing him. So the first solid chunk of the book is a flashback of Nigel's life since arriving here at the Galactic Center. Amazingly enough, the man changed! He's gone from being a jerk to a curmudgeon. Yes, that's an improvement. He's been humbled by marriage and parenthood, not to mention the discoveries made at the Galactic Center and how humanity fits into the galactic pecking order. But loss probably shaped him the most. This Nigel I liked, but I couldn't help but feel that the guy is a stand-in for Benford himself.

But the Mechanicals get the upper hand, errr appendage, and Toby is off on his own, wandering through those volatile estys again, trying to find his father or, at least, other Bishops. At one point, the whole thing transforms into the sci-fi adventures of Huckleberry Finn on the space-time-river equivalent of the Mississippi. I really wondered where Benford was going with this. It had its moments but it seemed like a distraction. Ultimately, this section comes to an abrupt end, and Toby is reunited with Killeen.

There's a final showdown with the Mantis, which was needed as the thing was responsible for so much suffering. The method of resolution was unexpected, but fitting. Afterwards, there's a bit of a long epilogue as we see glimpses of our main characters' lives. I found it to be a bit sad. There is no "happily ever after," but there is an after. And the takeaway borrows thematically from Shakespeare:

All the world's a stage,Benford could be considered guilty of meandering around with metaphysical speculation about higher lifeforms, but I can forgive him for that. We humans have this arrogance that the world—you could argue the universe—revolves around us. We are blissfully ignorant of older and far more advanced lifeforms in the universe, and our narcissism boasts that they don't exist because we don't have proof of them having visited us, as if we were so special that we merited being fawned over. It's a conceit that Benford doesn't ascribe to.

And all the men and women merely Players;

3.75 stars

\_/

DED

West

Germany, 1949. Former actor Max Kaspar suffered greatly in the Second World War. Now he owns a nightclub in

Munich—and occasionally lends a hand to the newly formed CIA. Meanwhile, his brother Harry has ventured

beyond the Iron Curtain to rescue an American scientist. When Harry is also taken captive, Max resolves to

locate his brother at all costs. The last thing he expects is for Harry to go rogue.

West

Germany, 1949. Former actor Max Kaspar suffered greatly in the Second World War. Now he owns a nightclub in

Munich—and occasionally lends a hand to the newly formed CIA. Meanwhile, his brother Harry has ventured

beyond the Iron Curtain to rescue an American scientist. When Harry is also taken captive, Max resolves to

locate his brother at all costs. The last thing he expects is for Harry to go rogue.

Trying

to escape the relentless mechs, the last humans from the planet Snowglade take their ancient starship on a

dangerous course straight into the Eater, the black hole at the galactic center. Hungry and desperate,

the refugees begin to question the leadership of Captain Killeen, who believes the center holds their

one hope of survival. Meanwhile, Killeen's son Toby struggles with the microchips that were implanted

in his spine—a technology that now threatens his sanity. Caught between their genocidal

pursuers and peril in the galactic center, Killeen and Toby bring humanity to its final destiny.

Trying

to escape the relentless mechs, the last humans from the planet Snowglade take their ancient starship on a

dangerous course straight into the Eater, the black hole at the galactic center. Hungry and desperate,

the refugees begin to question the leadership of Captain Killeen, who believes the center holds their

one hope of survival. Meanwhile, Killeen's son Toby struggles with the microchips that were implanted

in his spine—a technology that now threatens his sanity. Caught between their genocidal

pursuers and peril in the galactic center, Killeen and Toby bring humanity to its final destiny.

Galactic

Center series book #4.

Galactic

Center series book #4. This

one starts out well, is muddled in the middle, and then ends a bit disappointingly.

This

one starts out well, is muddled in the middle, and then ends a bit disappointingly.

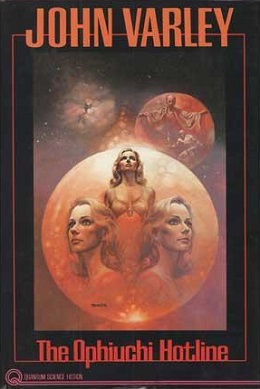

After

supremely advanced aliens invade Earth to liberate the planet's intelligent species—whales and dolphins—the

majority of humankind is exiled into space, where, by means of bioengineering, they begin to adapt to and thrive in

their unforgiving environments. Cutting-edge tech means that they can modify body parts, regularly store their

memories for cloning purposes and even merge with seemingly benevolent alien beings (known as symbs) to create

another entity altogether. The discovery of a steady—and mostly indecipherable—stream of data

originating from a star system 17 light-years away offers some kind of hope of advancing the species and

retaking the homeworld. But when the novel's protagonist (a series of successive clones named Lilo) travels

out to 70 Ophiuchi, what she finds may not be salvation for the human species but its damnation.

After

supremely advanced aliens invade Earth to liberate the planet's intelligent species—whales and dolphins—the

majority of humankind is exiled into space, where, by means of bioengineering, they begin to adapt to and thrive in

their unforgiving environments. Cutting-edge tech means that they can modify body parts, regularly store their

memories for cloning purposes and even merge with seemingly benevolent alien beings (known as symbs) to create

another entity altogether. The discovery of a steady—and mostly indecipherable—stream of data

originating from a star system 17 light-years away offers some kind of hope of advancing the species and

retaking the homeworld. But when the novel's protagonist (a series of successive clones named Lilo) travels

out to 70 Ophiuchi, what she finds may not be salvation for the human species but its damnation.

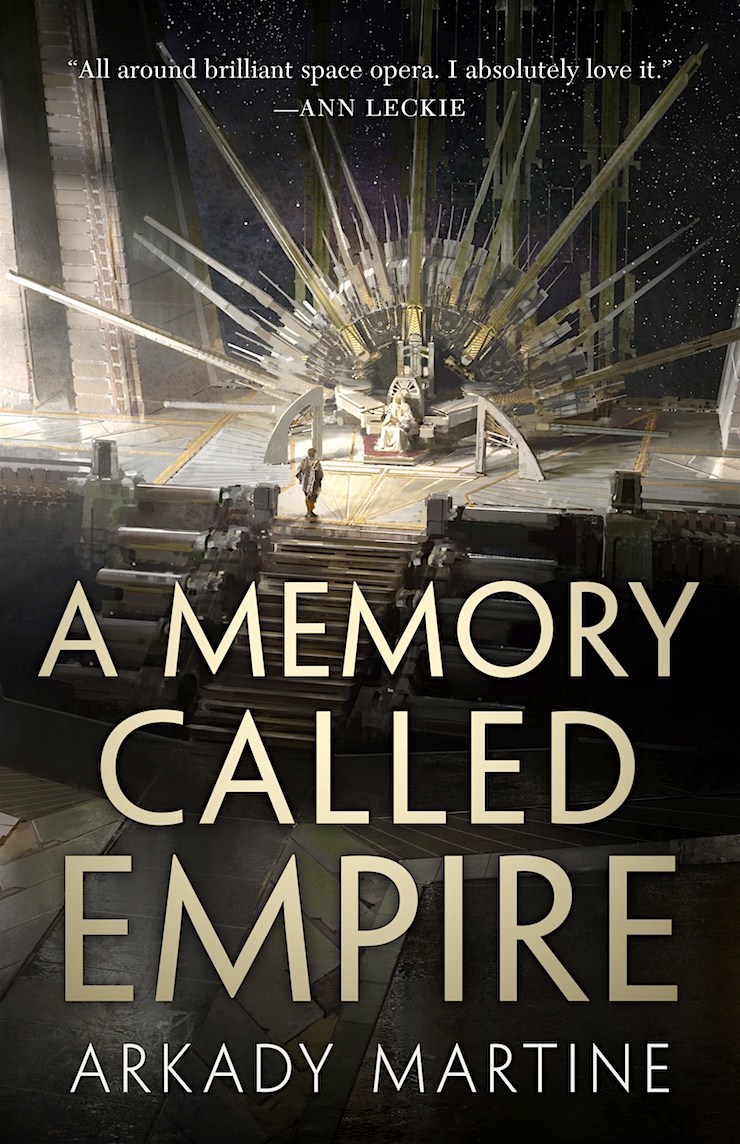

Ambassador

Mahit Dzmare arrives in the center of the multi-system Teixcalaanli Empire only to discover that her predecessor, the

previous ambassador from their small but fiercely independent mining station, has died. But no one will admit that

his death wasn't an accident—or that Mahit might be next to die, during a time of political instability in

the highest echelons of the imperial court.

Ambassador

Mahit Dzmare arrives in the center of the multi-system Teixcalaanli Empire only to discover that her predecessor, the

previous ambassador from their small but fiercely independent mining station, has died. But no one will admit that

his death wasn't an accident—or that Mahit might be next to die, during a time of political instability in

the highest echelons of the imperial court.